Earth’s ozone layer is failing to heal — and scientists don’t know why , II Ozone layer declining over populated zones , II Celebration over a shrinking ozone hole may have been premature

The rescue of the planet’s protective ozone layer has been hailed as one of the great success stories of modern environmental regulation — but on Monday, an international team of 22 scientists raised doubts about whether ozone is actually recovering as expected across much of the world.

“We’ve detected unexpected decreases in the lower part of the stratospheric ozone layer, and the consequence of this result is that it’s offsetting the recovery in ozone that we had expected to see,” said William Ball, a scientist with the Physical Meteorological Observatory in Davos, Switzerland.

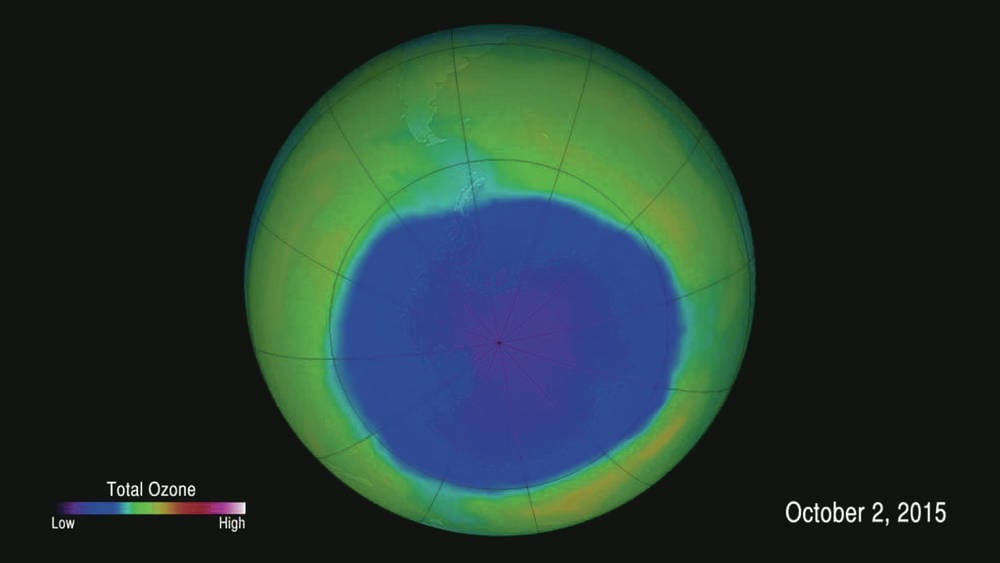

In 1987, countries of the world agreed to the Montreal Protocol, a treaty designed to phase out chlorofluorocarbons, or CFCs, responsible for destroying ozone in the stratosphere. The protocol has worked as intended in reducing these substances, and early healing of the ozone “hole” over Antarctica has been subsequently hailed by scientists.

But the study by Ball and his colleagues — a team of scientists including researchers based in the United States, Britain, Canada, Switzerland, Sweden and Finland — focused instead on the lower latitudes where more humans live. The research was published in Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics on Tuesday.

There, the scientists found a relatively small but hard-to-explain decline of ozone in the lower part of the stratosphere, the layer of the atmosphere that extends from about six miles to 31 miles above the planet’s surface, since the year 1998. Meanwhile, the upper stratosphere has been recovering.

“The precise cause of the trend is unknown but could be related to changes to the stratospheric circulation, which has a large influence on how ozone is distributed,” said Ryan Hossaini, an ozone expert at the University of Lancaster in Britain, who was not involved in the study, in an emailed comment. Those, in turn, could be tied to climate change.

There’s also a possibility that a new class of chlorine-containing chemicals not limited by the Montreal Protocol, dubbed “very short-lived substances,” could be contributing to the problem. The most prominent of these substances is dichloromethane, which has a wide range of industrial uses, including as a paint stripper.

Concentrations of the substance have been increasing in the atmosphere, and because of the compound’s relatively short lifetime, it is not regulated now under the Montreal Protocol.

At the same time, though, it’s not clear that there’s enough of it in the atmosphere to be causing what scientists are now observing.

“Although so-called very short-lived substances — some of which are increasing in the atmosphere — can contribute to ozone loss, they are very unlikely to be the main driver of the reported downward ozone trend based on their current abundance,” said Hossaini.

It all amounts to a mystery, but a troubling one because ozone protects life at the surface from incoming ultraviolet radiation, and any thinning of total ozone in the stratosphere is cause for concern.

“At the moment, there’s no proof of what’s causing it but there are some reasonable hypotheses that need to be investigated,” said Ball.

“We’re raising the alarm that we need to very rapidly investigate whether it’s the short-lived compounds, whether it’s a climate change response, whether our models aren’t quite doing the right job, or whether there’s something wrong with the data,” he said.

The political implications of the new research are not immediately clear, but Ball cautioned that it certainly does not mean that the Montreal Protocol isn’t working. It just means scientists must figure out what is actually going on — the cause of the new trend “urgently need to be established,” the new study says.

In the meantime, the new research raises questions about whether additional extensions of the protocol, which is designed to be updated based on new scientific developments, may be necessary to deal with the new findings of an ozone downtrend in the lower stratosphere.

“The future evolution of ozone layer will depend on the interplay between emissions of non-Montreal Protocol controlled [ozone-depleting substances], and on what happens with our climate,” said Paul Young, a climate scientist also based at Lancaster University, in an emailed comment.

In 2016, environmental scientists celebrated victory in an almost-two-decade battle. The stratospheric ozone layer—a blanket of molecules made up of three oxygen atoms that protect the planet from some of the sun’s ultraviolet rays—was finally rebounding. It seemed like international collaboration had paid off: The Montreal Protocol, a multilateral treaty that restricted the problematic chemicals that were putting holes in the ozone around the poles, seemed to be working, and the layer was bouncing back.

But maybe scientists spoke too soon.

Ozone is like real estate: Location is everything. There’s some ozone present in the troposphere, the air around us, but it’s generally a bad thing when it’s down here. It’s the main component of smog, detectable to humans via a burnt, acrid smell. But in the air roughly six to nine miles (10 to 15 km) above us, it’s life-sustaining. It’s essentially an all-organic sunscreen that prevents the most dangerous of the sun’s ultraviolet rays from reaching the planet—and us. Without it, we’d see much higher rates of skin cancer, and crop failures globally.

A paper published (paywall) Feb. 6 by a team including researchers from NASA and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration found the Montreal Protocol has been working. Their work analyzed the large, middle part of the planet as opposed to just the poles, where the vast majority of us live. It slowed the decline of the ozone from 5% between 1970 and 1988 to just 0.5% from 1988 and 2016, and it regenerated the ozone near the North and South poles. But that improvement hasn’t stopped the ozone layer’s dip entirely. There has been a slight uptick of ozone in the air closest to the Earth’s surface (probably from pollution), and a decrease of ozone in the closest layer of the stratosphere.

“This is surprising, because we would have expected to also see this [region’s ozone] stop decreasing,” William Ball, a researcher in atmospheric physics at ETH Zürich and lead author of the paper, told Scientific American. What’s worse, it’s not totally clear why the stratospheric ozone keeps withering away, which means it’ll be harder for scientists to stop or reverse this trend.

At the moment, Ball told Scientific American, there’s no reason to panic. In total, the protective ozone of our planet is stable. But other scientists are concerned about what may happen if humans don’t ramp up environmental regulation to protect this atmospheric layer.

“This study is scary,” Bill Laurence of James Cook University, who is unaffiliated with the study, told Cosmos magazine. “Until we understand what’s really happening you’d be silly to sun yourself, except in polar regions…We might be entering the age of the unfailing sunburn.”

In 2016, environmental scientists celebrated victory in an almost-two-decade battle. The stratospheric ozone layer—a blanket of molecules made up of three oxygen atoms that protect the planet from some of the sun’s ultraviolet rays—was finally rebounding. It seemed like international collaboration had paid off: The Montreal Protocol, a multilateral treaty that restricted the problematic chemicals that were putting holes in the ozone around the poles, seemed to be working, and the layer was bouncing back.

But maybe scientists spoke too soon.

Ozone is like real estate: Location is everything. There’s some ozone present in the troposphere, the air around us, but it’s generally a bad thing when it’s down here. It’s the main component of smog, detectable to humans via a burnt, acrid smell. But in the air roughly six to nine miles (10 to 15 km) above us, it’s life-sustaining. It’s essentially an all-organic sunscreen that prevents the most dangerous of the sun’s ultraviolet rays from reaching the planet—and us. Without it, we’d see much higher rates of skin cancer, and crop failures globally.

A paper published (paywall) Feb. 6 by a team including researchers from NASA and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration found the Montreal Protocol has been working. Their work analyzed the large, middle part of the planet as opposed to just the poles, where the vast majority of us live. It slowed the decline of the ozone from 5% between 1970 and 1988 to just 0.5% from 1988 and 2016, and it regenerated the ozone near the North and South poles. But that improvement hasn’t stopped the ozone layer’s dip entirely. There has been a slight uptick of ozone in the air closest to the Earth’s surface (probably from pollution), and a decrease of ozone in the closest layer of the stratosphere.

“This is surprising, because we would have expected to also see this [region’s ozone] stop decreasing,” William Ball, a researcher in atmospheric physics at ETH Zürich and lead author of the paper, told Scientific American. What’s worse, it’s not totally clear why the stratospheric ozone keeps withering away, which means it’ll be harder for scientists to stop or reverse this trend.

At the moment, Ball told Scientific American, there’s no reason to panic. In total, the protective ozone of our planet is stable. But other scientists are concerned about what may happen if humans don’t ramp up environmental regulation to protect this atmospheric layer.

“This study is scary,” Bill Laurence of James Cook University, who is unaffiliated with the study, told Cosmos magazine. “Until we understand what’s really happening you’d be silly to sun yourself, except in polar regions…We might be entering the age of the unfailing sunburn.”

The ozone layer that protects life on Earth from deadly ultraviolet radiation is unexpectedly declining above the planet's most populated regions, according to a study released Tuesday.

A 1987 treaty, the Montreal Protocol, banned industrial aerosols that chemically dissolved ozone in the high atmosphere, especially above Antarctica.

Nearly three decades later, the "ozone hole" over the South Pole and the upper reaches of the stratosphere are showing clear signs of recovery.

The stratophere starts about 10 kilometres (six miles) above sea level, and is about 40 kilometres thick.

At the same time, however, ozone in the lower stratosphere, 10-24 kilometres overhead, is slowly disintegrating, an international team of two dozen researchers warned.

"In tropical and middle latitudes" -- home to most of humanity -- "the ozone layer has not started to recover yet," lead author William Ball, a researcher at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich, told AFP.

"It is, in fact, slightly worse today than 20 years ago."

At its most depleted, around the turn of the 21st century, the ozone layer had declined by about five percent, earlier research has shown.

The new study, based on multiple satellite measurements and published in Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics, estimates that it has now diminished an additional 0.5 percent.

If confirmed, that would mean that the level of ozone depletion is "currently at its highest level ever," Ball said by phone.

The potential for harm in lower latitudes may actually be worse than at the poles, said co-author Joanna Haigh, co-director of the Grantham Institute for Climate Change and the Environment in London.

"The decreases in ozone are less than we saw at the poles before the Montreal Protocol was enacted, but UV radiation is more intense in these regions and more people live there."

Two possible suspects for this worrying trend stand out, the study concluded.

- 'Concerned, but not alarmed' -

One is a group of chemicals used as solvents, paint strippers and degreasing agents -- collectively known as "very short-lived substances", or VSLSs -- that attack ozone in the lower stratosphere.

A recent study found that the stratospheric concentration of one of such ozone-depleting agent, dichloromethane, had doubled in just over a decade.

Unlike the long-lived chlorofluorocarbons, or CFCs, that began tearing at the ozone layer in the 1970s, this new family of chemicals only persists 6-12 months. They are not covered by the Montreal Protocol.

"If it is a VSLS problem, this should be relatively easy to deal with," said Ball.

"You could apply an amendment to the Protocol and get these things banned."

The other possible culprit of the renewed breakdown of the ozone layer is global warming.

Climate change models do suggest that shifts in the way air circulates in the lower stratosphere will eventually affect ozone levels, starting with the zone above the tropics, where the substance forms.

But that change was thought to be decades away, and was not expected to reach the middle latitudes between the tropics and the polar regions.

"If climate change is the cause, it's a much more serious problem," said Ball, adding that scientists disagree as to whether the stratosphere is already responding in a significant way to climate change.

"We should be concerned but not alarmed," Ball continued.

"This study is waving a big red flag to the scientific community to say, 'there's something going on here that doesn't show up in the models'."

Ball and colleagues encouraged other researchers to duplicate their results, and drive down the level of uncertainty.

They also called for data-gathering missions -- by balloon or airplane -- to measure more precisely the level of VSLSs in the upper atmosphere.

At the same time, they said, scientists need to reevaluate the complex interplay of cause-and-effect in the lower stratosphere to see if models to date have missed telltale signals showing a link with climate change.

A 1987 treaty, the Montreal Protocol, banned industrial aerosols that chemically dissolved ozone in the high atmosphere, especially above Antarctica.

Nearly three decades later, the "ozone hole" over the South Pole and the upper reaches of the stratosphere are showing clear signs of recovery.

The stratophere starts about 10 kilometres (six miles) above sea level, and is about 40 kilometres thick.

At the same time, however, ozone in the lower stratosphere, 10-24 kilometres overhead, is slowly disintegrating, an international team of two dozen researchers warned.

"In tropical and middle latitudes" -- home to most of humanity -- "the ozone layer has not started to recover yet," lead author William Ball, a researcher at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich, told AFP.

"It is, in fact, slightly worse today than 20 years ago."

At its most depleted, around the turn of the 21st century, the ozone layer had declined by about five percent, earlier research has shown.

The new study, based on multiple satellite measurements and published in Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics, estimates that it has now diminished an additional 0.5 percent.

If confirmed, that would mean that the level of ozone depletion is "currently at its highest level ever," Ball said by phone.

The potential for harm in lower latitudes may actually be worse than at the poles, said co-author Joanna Haigh, co-director of the Grantham Institute for Climate Change and the Environment in London.

"The decreases in ozone are less than we saw at the poles before the Montreal Protocol was enacted, but UV radiation is more intense in these regions and more people live there."

Two possible suspects for this worrying trend stand out, the study concluded.

- 'Concerned, but not alarmed' -

One is a group of chemicals used as solvents, paint strippers and degreasing agents -- collectively known as "very short-lived substances", or VSLSs -- that attack ozone in the lower stratosphere.

A recent study found that the stratospheric concentration of one of such ozone-depleting agent, dichloromethane, had doubled in just over a decade.

Unlike the long-lived chlorofluorocarbons, or CFCs, that began tearing at the ozone layer in the 1970s, this new family of chemicals only persists 6-12 months. They are not covered by the Montreal Protocol.

"If it is a VSLS problem, this should be relatively easy to deal with," said Ball.

"You could apply an amendment to the Protocol and get these things banned."

The other possible culprit of the renewed breakdown of the ozone layer is global warming.

Climate change models do suggest that shifts in the way air circulates in the lower stratosphere will eventually affect ozone levels, starting with the zone above the tropics, where the substance forms.

But that change was thought to be decades away, and was not expected to reach the middle latitudes between the tropics and the polar regions.

"If climate change is the cause, it's a much more serious problem," said Ball, adding that scientists disagree as to whether the stratosphere is already responding in a significant way to climate change.

"We should be concerned but not alarmed," Ball continued.

"This study is waving a big red flag to the scientific community to say, 'there's something going on here that doesn't show up in the models'."

Ball and colleagues encouraged other researchers to duplicate their results, and drive down the level of uncertainty.

They also called for data-gathering missions -- by balloon or airplane -- to measure more precisely the level of VSLSs in the upper atmosphere.

At the same time, they said, scientists need to reevaluate the complex interplay of cause-and-effect in the lower stratosphere to see if models to date have missed telltale signals showing a link with climate change.

No comments

Post a Comment